The following article is part of the Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Volumues 24-25. The Art Bulletin is published annually and contains articles on the history and theory of art relating to the collections of the Nationalmuseum.

The Art Bulletin contains in-depth studies on the most significant acquisitions in the form of scientific articles and an account of all the museum's purchases and donations during the specified year. You can download a pdf-version of the article here.

You can even download the whole publication here

Magnus Olausson Director of Collections

Carl-Johan Olsson Curator, Paintings and Sculpture

As the traditional academic hierarchy of artistic subjects crumbled during the French Revolution, various forms of genre painting experienced an upsurge in interest. In particular, there was a fascination with city views and representations of spatiality. These images of everyday life are entirely unsentimental. They are like a peep show, with openings onto reality.

Perspective and light are important elements in generating the sense of illusion they convey. Ever since the Renaissance and the development of one-point perspective, artists have been fascinated by different ways of creating illusions of space. In the later part of the 18th century, tourism gave rise to a market for views from cities such as Paris. Many of the artists who produced them had received their training as perspective painters in the theatre. Some of them would go on to develop the panorama, a 360-degree view consisting of painted scenes arranged round the walls of a circular structure, with space in the middle for the viewing public. These paintings usually showed views of cities from high vantage points, or dramatic contemporary events such as fires and battles.

The leading panorama painter in Paris after 1800 was Pierre Prévost (1764–1823). His pupils included two artists who were previously unrepresented in the Nationalmuseum’s collections: Étienne Bouhot (1780–1862) and Charles-Marie Bouton (1781–1853). Both were celebrated figures in their day, but have since fallen into undeserved obscurity. They had both worked on perspective views together with Prévost. (cf. Étienne Bouhot 1780–1862, Sandrine Balan (ed.), Musée de Semur-en-Auxois 2001, p. 31.)

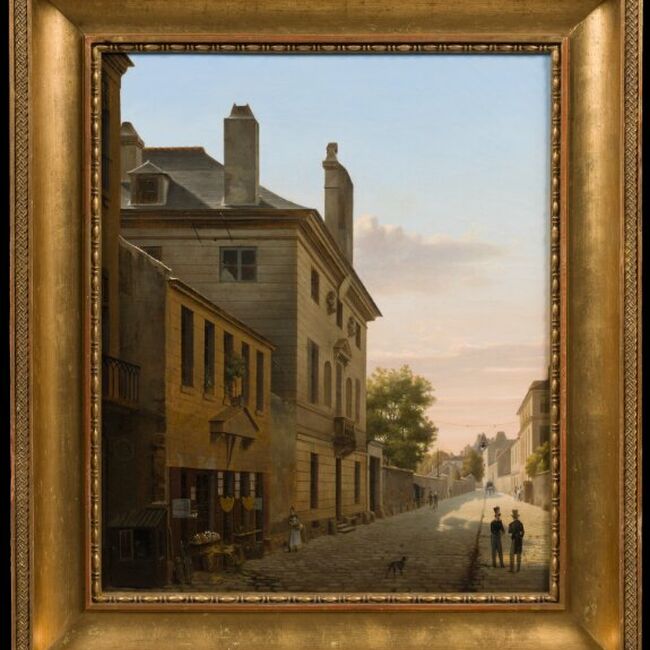

Bouhot exhibited his paintings from the 1808 Salon onwards, with an emphasis on views of Paris. The latter demonstrate a new eye for the city. We still see the famous buildings, but painted now from unusual angles or in unexpected perspective. Archways are often used to frame well-known monuments. There is also room here for the world of ordinary people, with its backyards, outhouses and other nooks and crannies. It is this sense of the everyday that Bouhot has captured in his image of a street in Paris (Fig. 1).

Here, details are rendered with meticulous precision, as is the play of light and shadow. Historicising genre painting was not alone in drawing inspiration from 17th-century Dutch art; topographical subjects did so to no less a degree. Bouhot’s technique also recalls the almost porcelain-like surfaces of the Leiden fijnschilder tradition. Staffage figures reinforce the illusionary effect and a strong sense of presence. They help to create depth, but are also part of a social context. Placed on different planes, these figures are like actors on a stage. Étienne Bouhot became very popular with the leading collectors of the time, including the Duke of Orléans, the future King Louis-Philippe I ( Valérie Bajou, “A Hagiographic Collection: Remarks on the Taste of Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans”, Getty Research Journal, no. 5 (2013), pp. 60–61.).

The Duke, who would brook no competition from other art buyers unless they were members of the royal family, had, by his persistence, managed to secure two paintings by Bouhot in connection with the Salon of 1817 (Now in the Musée Carnavalet; see Bajou 2013, p. 61. Cf. Étienne Bouhot 1780–1862, Sandrine Balan (ed.), Musée de Semur-en-Auxois 2001, p. 39). This resulted in a commission from him the same year for a painting of The Great Staircase of the Palais-Royal. LouisPhilippe, who showed a genuine interest in Bouhot’s work on the interior from his own palace, would come to converse with him daily in his improvised studio in the apartments of Princess Adélaïde. Perhaps it was in connection with these meetings that Bouhot presented the Duke with his sketch drawing for the painting recently acquired by the Nationalmuseum. (Étienne Bouhot, “Vue d’une rue dans Paris”, c. 1818, pen and wash in brown ink, 21.9 x 26.5 cm, Beaussant-Lefèvre SARL, 6 June 2014, lot 46, inscribed “à donner à Mons. Duc d’Orléans 1818”. The painting by Bouhot was exhibited under the title “Vue de la maison Bellechasse, rue Saint-Dominique” at the Salon 1824, (no 232). The Pavillon de Bellechasse was designed by the architect Bernard Poyet for the children of the Duke of Chartres, built c. 1778–79. It was situated at 11 bis, rue Saint-Dominique. The Pavillon de Bellechasse was destroyed in 1905. Cf. LouisPhilippe l’homme et le roi 1773–1850, (exh.cat.), Archives nationales, Paris 1974–75, p. 36. We are greatly indebted to M. Gérald Lefebvre in Bruxelles for having identified the motif of Bouhot’s painting.)

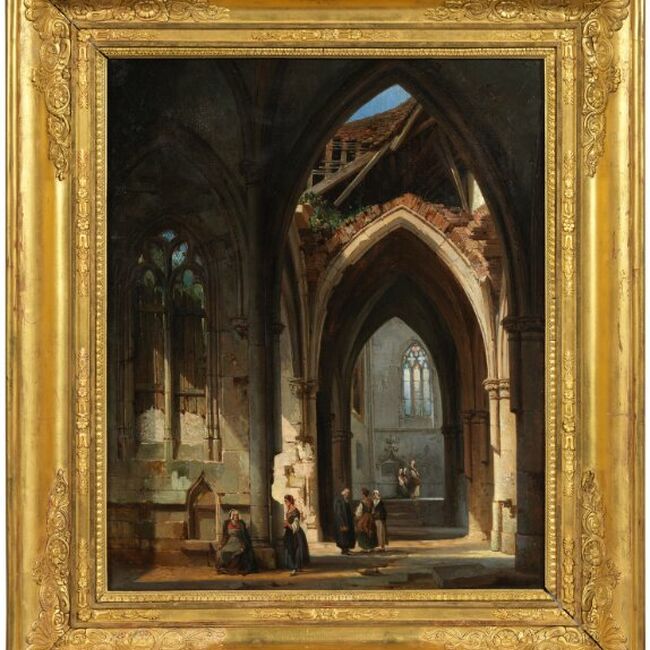

The artist might have thought that the motif would be tempting for the Duke since it showed the Pavillon de Bellechasse on rue Saint-Dominique, where he spent his childhood together with his siblings and the governess, la Comtesse de Genlis. Bouhot completed his painting of the Pavillon de Bellechasse in 1823. That was the same year as Bouhot lost his son Philibert, which was a contributory factor behind the artist’s eventual return to his native Burgundy and the town of Semur-en-Auxois. Nearby is the small village of Saint-Thibault, with its old Gothic parish church. The church was originally intended to have the proportions of a cathedral, but only a torso was ever built. Early on, the building attained the status of a national historic monument, and it was later restored by the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

In Bouhot’s painting (Fig. 2), recently added to the Nationalmuseum collection, we see the dilapidated state of the church before the restoration work began. His interior is not considered an entirely accurate rendering of the historical building and bears witness to the contemporary craze for the Gothic. It is also a slightly absurd reportage image of the state of the nation following the vandalism of the French Revolution. The vaults and roof are on the verge of collapse, yet the priest still stands calmly beneath them, talking to his parishioners. The blue sky and the light filtering through the broken window contribute to the evocative character of the painting.

In Charles-Marie Bouton’s First Communion in the Interior of the Crypt of the Church of St Roch, Paris (Fig. 3), too, we see the interplay of light and space, but here it is more complex in character. In the large central aisle of the church, to the left, a confirmation mass is under way. In the smaller adjoining spaces, parishioners are engaged in private prayer, while in the background we see Louis-Pierre Deseine’s sculpture group of the burial of Christ. These different representations of space and differing degrees of reality are achieved by an evocative treatment of light, entering through variously shaped skylights above. There is not just one perspective, but several, which together lend an air of mystery to the church interior. Inspiration for this remarkable twist on perspective probably came from Dutch 17th-century masters such as Gerard Houckgeest.8 Unsurprisingly, it was Charles-Marie Bouton, along with Louis Daguerre, who invented the diorama, a development on the panorama, with the addition of light to create an illusion of movement. Their joint creation, with two enormous screens, opened to the public in Paris in July 1823.9 With these three paintings, the Nationalmuseum is now able to present a phenomenon in pictorial art that would be of huge importance in the subsequent development of visual culture as a whole, set in motion by the invention of photography.